Globalisation rules! (Despite US unilateralism)

The United States’ newfound insularity doesn't mean the death of the globalised economy.

I can understand why people might see Trump’s America-first power grab as another stage of global economic disintegration. After all the US is the world’s single biggest economy, accounting for a quarter of global output. It’s grown faster than most other big economies in recent decades.

Commerce revolves around the US. By revenue, six of the world’s top ten businesses and 12 of the top 20 are American, led by Amazon and Walmart. The country’s rapacious consumers suck up 16% of the world’s products.

Like the Beatles, who only felt like they’d succeeded when they’d crossed the pond, until now you needed a US strategy if you wanted to make it big time.

The US runs the world’s international economic organisations based in Washington DC. The World Bank always has a US President. The International Monetary Fund is always European-led but the US is its largest shareholder.

Military and soft power back this economic clout. Hollywood and the US Agency for International Development (until now) helped win hearts and minds. If you don’t like US entertainment or commercial overtures: tough. “We’ll coup whoever we want!”

And it is true that Trump is radically reforming US international relations along several dimensions: trade, aid, international taxation; environment and the activities of multinationals abroad.

He’s slapped new tariffs on China and on global imports of steel and aluminium. He’s threatened tariffs of 25% on imports of cars, drugs and chips into the US. The US said that it will impose what it called 'reciprocal' tariffs on countries with which it runs trade deficits. Tariffs on Canada and Mexico were postponed.

With the stop order issued on USAID projects, despite a court ruling opposing the decision, the $71.9bn US international development assistance budget looks like to be severely reduced if not entirely curtailed, introducing considerable uncertainty.

The US effectively pulled out of a global tax cooperation treaty negotiated over the decade until 2023 at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Under the deal, if corporate profits were taxed below 15% in the country where the multinational was headquartered, signatories could potentially charge top-up levies. The treaty aimed to avoid tax revenue leakage and a race to the bottom on tax.

The reassessment of funding for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration can likewise be seen as a reorientation of policy toward the domestic agenda and away from the recognition of climate change and climate policy as a global good.

An executive order ending enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (1979) ends the legal situation whereby US companies abroad could be prosecuted at home for fraudulent or unethical dealings overseas. It again signals that the new administration will act unilaterally in the interests of domestic companies abroad.

As the US becomes a more uncertain trading and commercial partner with a me-first mindset, and as it erects trade barriers, the rest of the world will have no choice but to respond.

Trump’s protectionism will incentivise greater regional cohesion, encouraging some developing countries to seek new aid and trade partners, speeding offshoring and reshoring, and potentially diverting goods trade away from the US.

This will strengthen international groupings and regional trade blocs like the ASEAN–China Free Trade Area, Asia’s Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, and the African Continental free Trade Area. Goods trade is already taking on a more regional — rather than global — character.

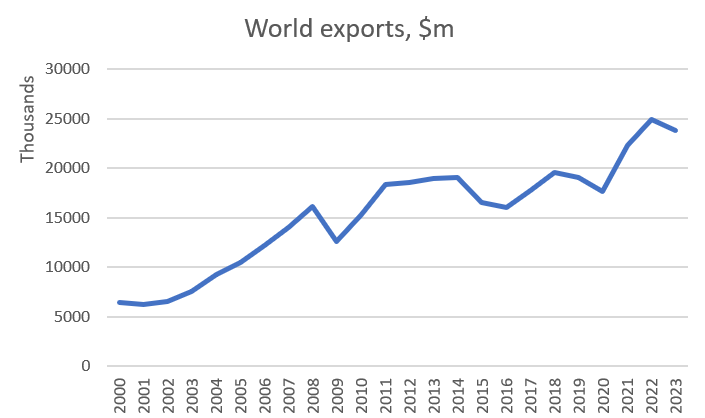

As the following figure shows, world merchandise exports were already slowing. By 2020 they’d barely climbed above their level in 2008 in the global financial crisis, although they subsequently increased and fell back a bit, to about 3.7 times their level in 2000 in nominal terms. There’s little doubt goods trade is wobbling.

When it comes to physical commerce, Trump’s unsophisticated new direction is self-defeating and will only exacerbate this trend, creating friction, more insularity and confusion. Other regional blocs and organisations will be forced to respond — in many cases by trading and cooperating more internally.

BRICS+ developed new impetus in January with the addition of Indonesia — the world’s fourth-largest country. China is already profiting from the US pullback by taking over in areas where the US withdrew. Trump has effectively handed more global influence to Beijing.

The character of global production is changing, with more regionalism — particularly as supply chains proliferate and Asia becomes the new centre of gravity. The international economy is decisively entering a new phase.

None of this is to underestimate the severity of what’s going on in the US. This is a coup, as the courageous journalist Carole Cadwalladr has repeatedly emphasised.

Still alive, despite the obituaries

But forecasts of globalisation’s imminent demise have repeatedly been proven wrong. For at least a decade soothsayers have foretold its passing, from The End of Globalisation to the Economist’s ‘slowbalisation’.

The eulogies were premature. Globalisation never had much to do with democracy anyway, nor need it have a material character.

The big secret behind Trump’s coup, backed as it is by the Silicon valley tech bros, is that globalisation is more and more driven by intangible forms of commerce, not goods. Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, Apple and Alphabet don’t much care about tariffs.

Their leaders, plus the tech venture capitalists like Andreesen Horowitz were happy to back Trump, despite previously professing their Democrat allegiances.

They’re prepared to go along with Trump’s power grab — and in Musk’s case, to lead it — because they think it’s in their interests. The administration’s brutal cost-cutting and further associated tax cuts for the super-rich and their companies will firm up their revenues. International financiers too, are cheering, because it allows them to extend their reach further into the global economy.

It’s a mistake to be drawn too much into debates over American decline, because globalisation was never about national borders — it was the internationalisation of capital and consumption. The interests of Chinese and US capitalists, for example, are often blurred.

Trump delayed Biden’s TikTok ban and said the US might buy it. Apple and Tesla have significant investments in China. Apple relies heavily on Chinese manufacturing for its products. Tesla has a Gigafactory in Shanghai.

Alibaba has been listed on the New York stock exchange for the last decade. Walmart buys most of its goods from China. Chinese investment in the US is large — from Treasuries to real estate to resources.

Economist and former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis is right that one of the main dynamics of globalisation has been what he calls the Global Minotaur, or the Chinese current-account surplus (the flip-side of a capital-account deficit) and the US deficit (a capital-account surplus).

China produces the goods that those rapacious American consumers demand, and China in turn invests the resultant earnings in safe American assets, largely US Treasury bonds. The two processes exist in a symbiosis that’s belied by the apparent public antagonism.

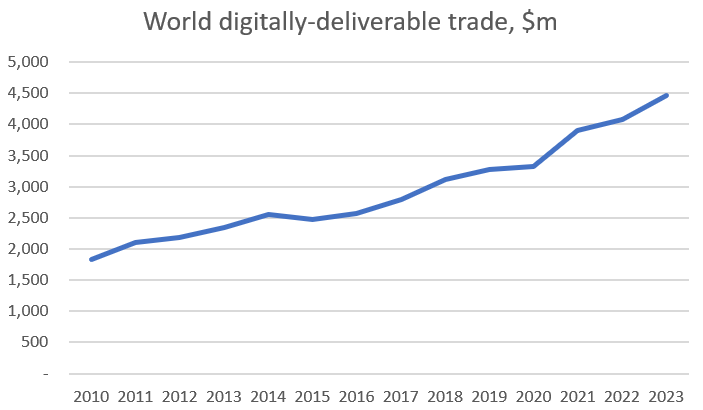

Globalisation’s persistence can be seen in the steady rise of services and digital trade, which has nearly tripled in the last 13 years, a much faster rate of expansion than for goods trade. The data are clear. Digitally-deliverable trade is roaring ahead.

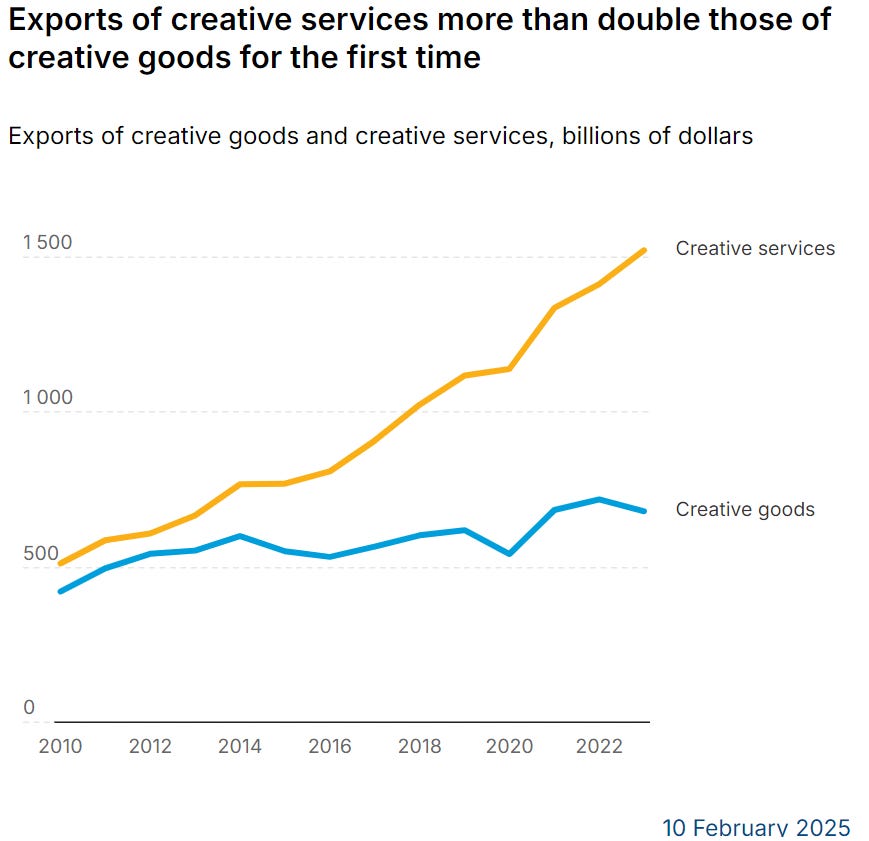

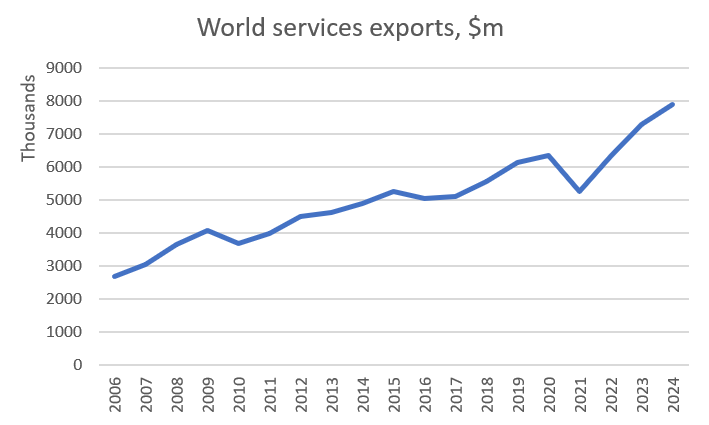

Services trade is equally buoyant, more than doubling in nominal terms since 2010 despite a downturn in the pandemic.

Exports of creative services are booming while exports of creative goods stagnate:

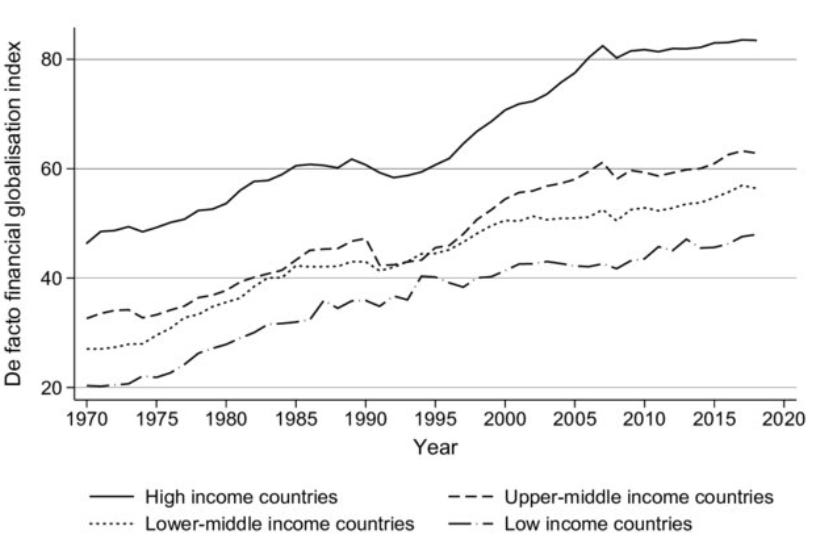

Financial globalisation stretches back decades. Although it can be measured in different ways, the various metrics mostly point to the same conclusion: an upward trend over at least half a century, with a couple blips in the early 1990s and during the financial crisis. The following graph shows the results of one attempt at a financial globalisation index.

To repeat, globalisation is about global capital and profit-generation, not about national boundaries. One of the reasons why Trump — propped up by Silicon valley — can erect such barriers to physical trade, is that they hardly affect the digital industry at all, which may be based in California but books much of its profit in other parts of the world like Ireland and other tax havens.

So what explains Trump’s nativist, me-first thuggery? Delving into his psychology is neither pleasant nor worthwhile. Part of his and his cronies’ motivations seem sadistic, designed to inflict pain on perceived opponents.

A lot of it’s clearly got nothing to do with economic theory (because the tariffs make little economic sense, except to his misguided trade adviser, former prison inmate Peter Navarro).

What seems to be going on is that Trump’s signalling a tough approach to his nativist base; overestimating American power; identifying levers to negotiate because he has a nakedly transactional mindset; and trying to bully and intimidate other countries.

Whether he’ll succeed remains to be seen. As i’ve already said, I think he underestimates the extent to which US trade barriers will compel others to look for new markets, trading more regionally or within alternative economic groupings.

Any one of a number of risks could derail Trump’s project. The tariffs could fuel inflation, prompting the Fed to keep interest rates higher for longer. Bitcoin or stocks could crash. The domestic economy might slow in coming years as his bad policies begin to take effect.

There’s a high chance that Trump’s clumsy brutality could backfire on himself, and, sadly, on many American people. I suspect that Musk’s overstepped the mark and tried to interfere in ways that even he might come to regret. His popularity may already be falling.

But the rest of the Silicon Valley broligarchy and their financiers might achieve their aims, which include avoiding their fair share of tax, shedding any responsibility for the weaker or less privileged, making sure their monopolies and social media empires remain unregulated, and consolidating their global fiefdoms.

For them, the rewards are high but risks associated with failure low. After all, most of them make the majority of their money outside the US. Globalisation is less and less about international trade in things, and more about intangible trade, particularly digitally-deliverable services. It’s long involved the free movement of capital flows.

And anyway there’s always some other part of the world to hold up the globalisation mantle. For what’s clear is that far from being on the sickbed, financial and techno globalisation are alive and well - they’re just evolving.

It has to be seen in the context of combined and uneven development. A comparison with the role of gravity in astrophysics and the formation and development of galaxies and so on is also useful. Its not one linear process of gravity pulling all matter together. It forms clumps, and those clumps tend to get bigger, then at various points, the clumps also interact, merge, or else act to pull apart other clumps and so on.

Nation states formed because the laws of commodity production and exchange, via competition led first to the development of capital, and then to the need to form larger single markets, with a level playing field policed by a single state. Then, as capital grew even larger - imperialism - the nation state became a fetter, and larger single markets states were required, formed either by war and annexation, or by voluntary agreement.

The actions of governments, even of the most powerful nation states such as the US, responding to or fermenting nationalist fervour, cannot change those underlying economic laws, and specific laws of capital. But, the way those laws play out is not pre-determined or fixed either. If it was the centripetal forces would already have created a global single market and state, not first nation states, an then multinational states/economic blocs.

I have often wondered why the EU has not developed its own globally competitive leaders in technology, to rival Microsoft etc., and the reason cannot be simply the existing monopolies, or lack of capability. It has and has had large tech companies, like ICL, Siemens, and so on, but it seems that, as with NATO, the EU has simply deferred to, and been happy to sit under the cover of US tech companies. I think the EU is likely to have to respond to Trump, not only in respect to NATO, but also in relation to technology by ending that situation, but as I have written recently the result of that is also likely to be a reorientation of Europe to those regional economic blocs - Eurasia - with which it shares land borders, and geographical proximity, which ha always been the main determinant of trade.