Stop doing stupid stuff

Unpredictability and instability may even be worse than tariffs

US tariffs will still hit several of the least developed countries hard, despite the US reducing them to 10% [NB. the US might raise them again again after 90 days].

Lesotho, where the original tariff would have been 50%, experiences the biggest reprieve, but its exporters will still face headwinds.

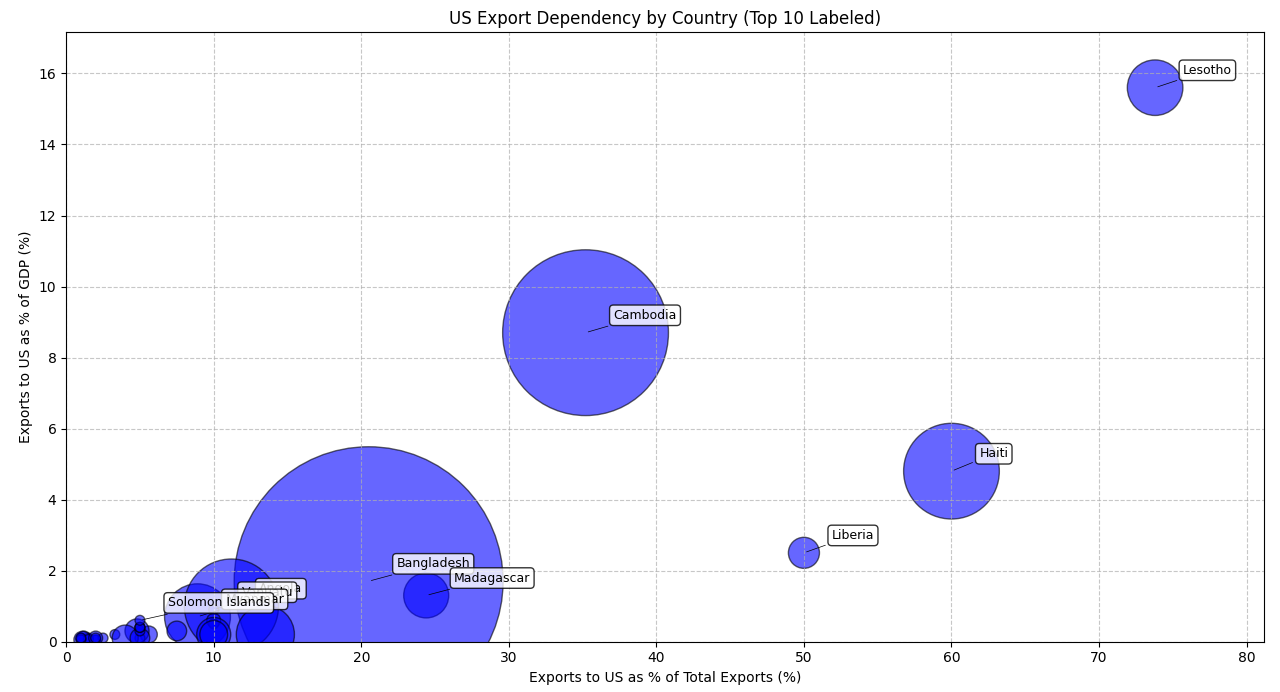

Of the LDCs, Lesotho is the most exposed to US exports. Nearly three-quarters of its exports go to the US, amounting to 16% of its GDP.

The economic damage before the high tariff would’ve been high — at an estimated tenth of GDP. Now, the the impact could amount to a couple of percentage points of GDP.

This will still mean job losses or furlough, higher poverty, and further instability for a struggling economy. It’s wrong to imagine that the threat has receded.

Haiti and Cambodia, too, remain exposed. Although a relatively small proportion of Haiti’s economy is reliant on US exports (about 5%), its total export basket is heavily US-dependent.

Cambodia is more reliant on the US but its exports more geographically diversified (mainly toward Europe). Bangladesh’s total exports are the highest of any LDC (shown by the size of the bubble in the diagram below) but its reliance on the US is lower, at only about 2% of GDP.

The following diagram shows that tariffs will continue to affect the LDCs most exposed to the US.

But it’s the unpredictability that’s the worst. Effectively the US has thrown the African Growth and Opportunities Act (AGOA) into question, ending the situation whereby African goods faced duty-free entry into the US. Renewal already looked unlikely.

AGOA’s vulnerability to non-renewal was always its Achilles heel relative to the European Everything But Arms (EBA) initiative, which was written into law in 2001 and remained less likely to be rescinded. AGOA’s demise means that some trade will be diverted toward Europe.

Everyone knows businesses hate uncertainty — why would you expand your US-export orientated investment in Lesotho now, when Trump might change his mind next week? Few existing or potential investors anywhere, never mind in the LDCs, will see the US as a source of stability.

And the effect of the tariffs on the US economy is the biggest source of uncertainty. Never mind a 10% tariff, a US — or global — recession is a much scarier proposition. Lower growth in the world’s economic engine will have the biggest effect on LDCs as all economies lose out.

US consumers are already cutting back. Treasury bond yields have spiked (which forced Trump’s about-face). The dollar is in decline, further reducing US buying power. As stagflation beckons, few should look to the US for support.

As in previous crises, clumsy and short-termist mismanagement by the world’s biggest economies and the global financial institutions that they control are the worst problems for the LDCs.

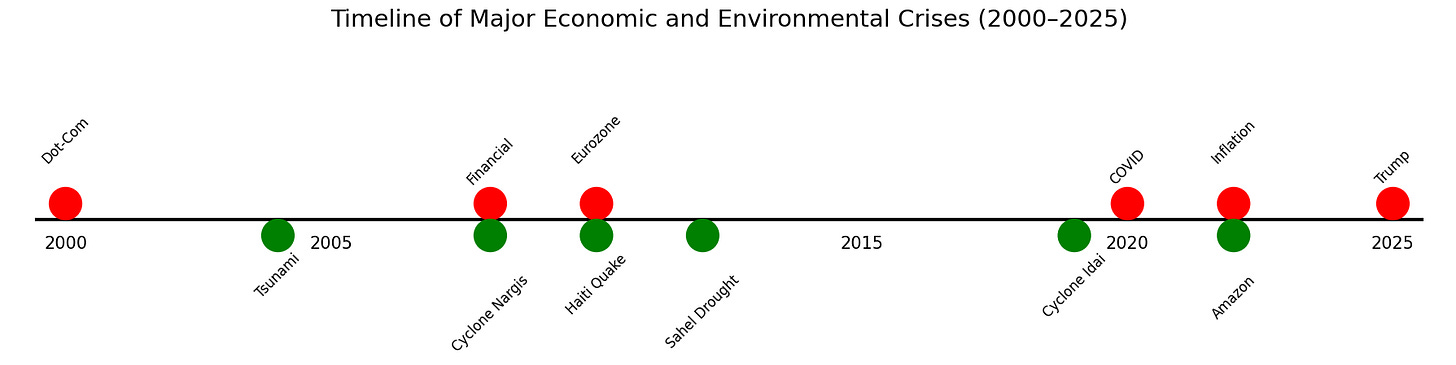

A quarter century of crisis

At least a dozen major environmental and economic crises have whacked the LDCs in the last quarter-century, often at the same time, starting with the dotcom crash in 2000. The Indian ocean Tsunami was in 2005. Then came the devastation of the global financial crisis in 2008. Cyclone Nargis the same year was the worst natural disaster in the history of Myanmar.

Many other environmental or weather-related events severely affected smaller countries - like the Western Pacific’s cyclone Pam in 2015, which chopped off half of Vanuatu’s GDP in a year.

The eurozone calamity from 2009-10 hit commodity and tourism demand worldwide — with a major fallout for LDCs. An earthquake struck Haiti. The drought in the Sahel followed, then the big three: Covid-19, inflation and now Trump.

Of course earthquakes and tsunamis aren’t human-made, but most of the others are, and they’re the result of mismanagement — either economic or environmental.

Global heating is perhaps the ultimate act of foot-shooting. It’s generated by the rich world and it’s hitting the poorest the most. Small, poorer countries have fewer resources to cope with the impact of crises. Infrastructure is more fragile. Losing a job can mean starvation. No safety nets exist.

So Trump’s tariffs aren’t only a self-inflicted wound. They’re a blow inflicted on the world’s most vulnerable. And just as many of the crises of the past quarter century could have been avoided or ameliorated, this latest bout of policy stupidity wasn’t inevitable.

I’ve long thought that we don’t need to get too clever in our theories about how to improve the relationship between the rich and poor countries (or core and periphery, developed and developing, or North and South — whichever couplet your theory demands).

No, one of the first and most achievable things would be for the rich world to stop doing supposedly self-interested but ill-considered things which have a disproportionate impact on the world’s poorest. Part of the fate of the LDCs lies in the hands of rich-world policymakers. They should stop doing stupid things.